- Home

- Ae-ran Kim

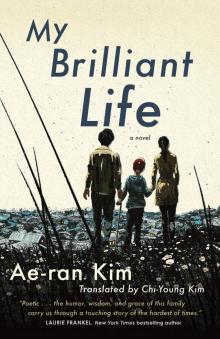

My Brilliant Life

My Brilliant Life Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author and Translator

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Tom Doherty Associates ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on Ae-ran Kim, click here.

For email updates on Chi-Young Kim, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Prologue

My parents were sixteen when they had me.

I turned sixteen this year.

I have no idea if I will make it to seventeen or eighteen.

That kind of thing isn’t in my power to decide.

All I know is that there isn’t a lot of time.

Children grow bigger and bigger.

And I grow older and older.

A day in my life is like an hour in someone else’s.

A year in my life is like a month in someone else’s.

Now I’ve become older than my dad.

My dad sees his future eighty-year-old face in mine.

I see my future thirty-two-year-old face in his.

A distant future and an unlived past gaze at each other.

And we ask:

Is sixteen the right age to become a parent?

Is thirty-two the right age to lose a child?

My dad asks me what I would want to be if I were reborn.

I respond loudly, Dad, I want to be you.

He asks why him, when there are better people in the world?

I say quietly, shyly, Dad, I want to be reborn as you and have me

To understand how you feel.

My dad cries.

This is the story of the youngest parents with the oldest child.

PART ONE

1

My grandmother had six children: five sons and a daughter. Once I asked, “Mom, why did Grandmother and Grandfather have so many kids when they never got along?” “Well—she said they did it once in a blue moon and each time she got pregnant.” My mom was the baby of the family and was known in her childhood as Princess Fuck; having grown up around foulmouthed men, she dropped curse words at every opportunity. I feel close to my mom when I think about the small, adorable girl she would have been, wandering around the village, swearing. She’s still feisty, but she must have toned down her vocabulary when she got knocked up and got kicked out of school, or when my dad was beaten to a pulp by her five brothers over it. Or maybe it was when she had to stare at the hospital bills she couldn’t afford.

* * *

From the very beginning, my grandfather didn’t like his son-in-law. For one, my dad, a kid who was still wet behind the ears, had gone and made another kid who was soaked behind the ears. My dad also couldn’t eke out a living, though that wasn’t all that unusual for a sixteen-year-old high school student. At their first encounter, my grandfather launched into a sullen interrogation. “So what are you good at?”

This was after a hurricane of tears and screams that accompanied the news of my mom’s pregnancy had subsided.

Kneeling before my grandfather, my dad was at a loss. “I’m good at Tae Kwon Do, sir.”

My grandfather grunted disapprovingly. While my dad’s Tae Kwon Do skills had landed him in the largest athletic program in the province, that didn’t make money.

My dad was made anxious by my grandfather’s silence. “Would you like to see?” He balled his fists, as if he were going to throw a punch at my grandfather, who flinched involuntarily.

“Are you saying you can make money with your fists?”

“Um, well, when I graduate I can work at a Tae Kwon Do studio…” He trailed off, knowing there was no chance he would be able to finish school.

My grandfather tried to give him another chance. “What else are you good at?”

Thoughts flew through my dad’s head. I’m good at Street Fighter. He couldn’t say that; his new father-in-law might punch him in the face. I’m good at talking back to teachers.… Even he knew that these were not the answers his father-in-law wanted. What am I good at? A few minutes of agony later, he finally admitted, “I’m not sure, sir.”

That was when he realized it. Oh. I’m good at giving up.

* * *

Later, my grandfather said mockingly, “He can’t do anything other than breed.”

“Well, that’s certainly a talent, too,” grumbled my grandmother.

Without speaking, my mom sat primly nearby, her bangs flattened and secured to one side by a pin in the style of the day.

My grandfather looked into the distance. “A poor man should at least have some kind of bravado. I don’t know. He’s like an idiot.” He sounded more disappointed in his daughter’s taste than in her actions.

But my grandfather had failed to recognize who my dad really was. Sure, he was an idiot, but he was brash and adventurous, the most dangerous kind of idiot. That was why he got into a fistfight with the officiant at his wedding, then abandoned his new wife to hang out with his buddies. That was also why he dabbled disastrously in a variety of ventures on the foolish recommendation of his friends. On a trip to Bulguksa Temple, he’d had our family motto, “Trust Between Friends,” calligraphed and framed at a souvenir shop and hung it proudly in our house.

My grandfather urged my dad to graduate. Since he would get kicked out of his program for impregnating a girl, he could enroll in a nearby school and at the very least get a diploma. Unfortunately, rumor and gossip travel at lightning speed and no school was interested in taking him, claiming that a student like my dad would damage their reputation and set a bad example for the other kids. My grandfather, who assumed his recommendation as a village leader would prevail, was humiliated by the rejection and ended up suggesting working in construction while studying for the high school equivalency exam. Though construction work was ostensibly a way for my dad to support his growing family, there had to be a part of my grandfather that wanted to make the boy who dared touch his daughter suffer for a few months. As my dad’s family was poor and unable to support us, he had to heed his father-in-law’s wishes.

Around that time, the county began a push to bring in tourists with the slogan “Daeho, a fun-loving city.” The village economy experienced a short-lived boost. Excavators, concrete mixers, and trucks drove into our quiet village. Everything was soon covered in dust. The construction company gave out free supplies—stationery, ballpoint pens, correction ink, colorful sticky notes, mechanical pencil lead refills, all imprinted with the company logo—to all the schools that might be impacted by construction. The villagers received detergent, cookware, and kitchen tools. But as with all things that are free in this world, there was a whiff of something unpleasant about the transaction.

The major project was enlarging the creek to enable sightseeing from a boat. Eventually, our village and a few neighboring ones would be submerged.

* * *

My grandfather, who had a head for numbers, built a small concrete-and-slate-roof house in their front yard for the

workers who swarmed in from other towns. He gave one room to my parents, and though there wasn’t much of a kitchen to speak of, and it was far too small, my parents say they never complained because they were living there for free. My dad went to work in construction with the itinerant laborers who lived in the concrete house with us. He was teased but beloved at work, with everyone calling him Han the Married Man. The village elders patted him on the back, saying, “Around here, you’re an adult when you get married,” and joked, “The Chois got a son-in-law for free!” My dad was briefly satisfied with his work. He enjoyed the men’s earthy talk, and had turned respectable in his in-laws’ eyes. Even before he got my mom pregnant, he’d wanted to quit Tae Kwon Do; he was tired of being ordered around. Now that he was out in the real world, working alongside real men, he wanted to climb up a peak, rip open his shirt, and roar, “This is real life!” But in just a few days, he realized how backbreaking it was to use his hands to make a living.

* * *

My dad learned about me in a café frequented by students, near the intercity bus terminal in town. My mom had gone on a few group dates there. Once, she’d gone there on a blind date with a boy who was in a biker gang. Afterward, he drove his motorcycle to her school and did wheelies in the yard, shouting “Mira! I love you!” before roaring away in a cloud of dust. All the girls named Mira—Kim Mira, Park Mira, and my mom, Choi Mira—were questioned by the teacher.

The group dates usually started at that café and ended with karaoke. Awkward boys who didn’t say a word in the café became extroverted when they gripped a mic. They would shove all the tables to one side of the dark, dank room and dance violently to Seo Taiji or Deux, singing, “Time will never stop. Yo!” or “Now I have to be brave to be able to have you.” A girl would sing the first few measures of a duet before furtively putting the mic down on a table, and a boy who liked her would grab the mic and sing the next verse. Boys fell first for my mom’s beauty and then for her voice. When she put down the mic, several hands would shoot out to grab it. Although there were a number of boys’ high schools in the area, few boys interested her. The students who studied practical subjects like agriculture were more outgoing and spent more lavishly, but she liked how confident humanities students were. My dad was the first boy she ever met who was in an athletic program, and they met not on one of those dates but in an unexpected place, by chance. Anyway, my mom thought my dad had the self-esteem of a smart kid but also the inferiority of being an athlete in a society that held scholars in high regard.

On the day my dad learned about me, my parents were sitting in the fairly empty café. He glanced at her, wondered why she was wearing such a thoughtful expression, and worried that she wanted to break up again. They hadn’t seen each other in a while, and she suddenly looked mature to him. She sipped her lemonade and licked her lips before she spoke.

“Daesu, come here.”

“Why?”

“Just do it.”

He leaned across the table.

She whispered in his ear, one hand covering her mouth. Her soft breath tickled the fuzz on his earlobe. He grinned, not concentrating on her words. Soon, his face turned pale. “Why did you wait so long to tell me?” he nearly shouted.

People turned to look.

“Why are you yelling?” my mom snapped, her voice even louder than my dad’s. “I hate when people yell!”

“Sorry, sorry.”

They put their sixteen-year-old heads together for a solution, but came up with nothing.

Eyes downcast, my dad toyed with a small parasol planted in his parfait. “Mira, I—” he began, launching into how much of a loser he was, how he could never be a good father, how he had no money, how he was afraid of disappointing people, and how, now that he was thinking about it, there were people in his family tree who might have had cancer. He rambled on incoherently.

My mom listened quietly until he finished. Gently, she said, “Daesu.”

“Yeah?”

“There’s this bug that camouflages itself with shit so it won’t get eaten by a bird.”

“And?”

“That’s you.”

* * *

One day, Han Sumi came up to my mom. “Mira, what’s going on with you?”

“Hmm? What do you mean?”

“You’re always falling asleep in class. And you’re not as chatty as you usually are.” Sumi, the class president and my mom’s best friend, was tasked with writing down the names of people who talked during class, and for the first time my mom’s name wasn’t on her list.

“Nothing’s going on.” My mom averted her gaze.

Sumi narrowed her eyes, quick to catch on to lies. “Come on. Tell me.”

Shoving her hands into her pockets, my mom leaned back. “What’s with you?”

“If you’re hiding something, don’t make it so obvious.”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“Seriously? I always tell you all of my secrets.”

My mom snorted. “Are you kidding? Oh, are you talking about how upset you are that you got bumped down to number three instead of being number one in the class? Thank you so much for entrusting me with such a huge secret.”

Sumi bit her lip. “Being number three is no joke, Mira.”

My mom answered with the soft voice she used when she was irritated. “Hey, Sumi?”

“Yeah?”

“Get lost.”

* * *

Of course, she didn’t mean that. The two were incredibly close; they’d gone to the same schools, ate lunch together daily, and went on group dates together. My mom wanted to tell Sumi everything after she slept with my dad. It all felt surreal; she was floating on air. She sat in the back of the class, jiggling her leg, watching the other girls as they focused on their books. Could they tell I slept with someone? she wondered. Guilt and superiority clung together to create an odd pattern in her heart. She’d lost something enormous, but she felt triumphant, not ashamed. She felt out of place. She was the only person in the whole class living in a different dimension. A few days later, she called Sumi out to the back, near the trash cans. She wanted to tell her; it was her duty to share her secret with her best friend. But as she was about to utter my dad’s name, Sumi began to bawl about her grades. “I’m so stressed out,” Sumi sobbed. “I don’t want to live if I have grades like these.”

My mom knew everything about Sumi’s problem. As people working for the construction company came from larger cities, local classrooms had seen a major shift in class rankings. More students had transferred in, students who had been studying hard since they were young. While the school administration was thrilled that average scores were boosted, the number one student in the village dropped to number three and number ten sank to fifteen. The worst in the class was still the worst but she too felt miserable about it, because being the worst out of fifty was far worse than being the worst out of forty-five. Sumi, who had always been the brightest in their village, had been mortally wounded by the drop in her stature. They had often heard about the tragedy of a village genius realizing she was nothing special once she moved to the big city, but it was even more unfair that the brilliant students were dethroned by interlopers, while minding their own business in their hometowns. After she was knocked off her pedestal, Sumi studied even harder than before, and though her scores climbed her rank remained the same.

“Mira.”

“What?”

“If you don’t want to tell me…”

“Yeah?”

“You know you don’t have to.”

My mom didn’t reply.

“But let me tell you what I do when I’m dealing with something.”

“I’m going to kill you if you tell me again that I just have to do my best,” my mom warned fiercely.

“God, no. Listen. I know all about doing your best. That didn’t do much for me, did it?”

My mom blinked a few times before nodding in comprehension.

“Anyway, whene

ver I have a problem I make a list. Pros and cons. Sometimes that helps me see the answer. Try it.”

* * *

It was the middle of the day and my dad was lying on his back on the floor of his room. A yellowing world map was tacked on the ceiling. His father had hung it up there when he entered elementary school, telling him to dream big. My dad hadn’t asked my mom to do anything after they parted ways at the café. He didn’t have the confidence to tell her to have it or to get rid of it, and didn’t know what the right choice would be. What would his life turn out to be? What would be the fate of the baby in my mom’s belly? He had no idea about any of it. The only thing he could fathom, however faintly, was that his life would get immensely difficult. He wanted my mom to make the decision. Then he would say, “That’s exactly what I was thinking,” and give her a hug, creating a lifelong shield from any sort of criticism. The most urgent issue at hand was financial. Regardless of which avenue they took, they needed money. Should he get a newspaper route or work as a restaurant delivery boy? No matter what kind of job he could finagle, he would have to get an advance on his paycheck. And he didn’t even have a driver’s license. The most realistic solution was to borrow the money, but he didn’t know anyone with that kind of cash. One guy in his class wore Calvin Klein briefs but he was unfortunately known for being stingy.

My dad had no one to lean on. He should have stopped himself in the heat of the moment. He was concerned about the scandal that would spread through town. Staring up at the ceiling at the wrinkled world map, he gazed at the five oceans, six continents. Six billion people. How did the world grow to have so many people? Naturally his thoughts drifted to people dating, their sexual desires, and their sex lives. His pants bulged, expanding gradually until the fabric was taut and strained. He wanted to cry; his desire had bloomed without regard to his predicament. Perhaps he would be enslaved by this desire for the rest of his life. And since he and Mira were already in this situation, maybe it wouldn’t be so bad to do it again.

My Brilliant Life

My Brilliant Life